Star of Empowerment

The Star of Empowerment is a roadmap that will help you understand human thought, behavior, and interactions better than ever before.

The Star will help you:

- Reduce frustration and anger

- Reduce that feeling of being lost

- Stop being manipulated

- Start making decisions out of choice and not fear

- Have more time to use how you choose

- Have more fun and enjoyment

- Have a greater peace of mind

“Continue having the best experience possible.” –Scott Folley

We all start out life asking “how.” How do I do this? How do I do that? How do I get this, and how do I get that? Then, we use that knowledge to pursue the things we desire. At some point in life, likely once we begin to understand cause and effect, the question “why” seems to be asked as much, if not more, than “how.” Why do people do this? Why do people do that? Why do I do what I do? And why did that happen? When you realize what I mean by we are all “having the best experience possible,” you will understand why people, like you and me, do what we do.

You might be asking yourself what this has to do with the Star of Empowerment. The Star will help you see how the concept of having the best experience possible explains human behavior. Before presenting the Star, I want to provide some background. For numerous reasons, I have spent quite a bit of my life asking why we all do what we do. In my quest, I have developed the Star, The Five Worlds, and what I have learned from a four-way stop as tools to explain how we think and why we do what we do.

The Star will help you understand how we think and our inner world. The Five Worlds will help you see the exterior world that we navigate with the Star. With the Star, you will see the ways you are being manipulated, learn how to quickly recognize it, and how to stop it if you choose to. Sometimes, it is fun just to play along when you know what is happening. It’s best to gain a good understanding of the Star and the inner world before moving on to the Five Worlds and the outer world.

The Pleasure Principal

If you are like me, you have probably heard many times about Freud’s pleasure principle. It’s a theory that all our decisions are made to avoid pain and gain pleasure, and that we will do much more to avoid pain than to gain pleasure. However, when you look around the world, this theory quickly falls apart. It seems to be one of those concepts that has been repeated so many times that people just assume it is correct. If this were true, we would all be lying in bed every day with the food or chemical of our choice and never leave the house. Why would people go to the gym and work out, or run marathons? If we are more inclined to avoid pain than gain pleasure, wouldn’t everyone just skip the gym or the race? It seems a lot more effort is being exerted in the pursuit of pain than avoiding it. If the theory were true that we do much more to avoid pain than gain pleasure, then there is a good chance I would not be here, as I am the sixth of seven kids. Seems like it would have been easy to skip those last few and avoid quite a bit of pain.

The Best Experience Possible

I have developed the “best experience possible” theory. Pain and pleasure are just guides to teach us and help us survive. Instead, our decisions, based on the knowledge and experience we have, are made in pursuit of the best experience possible. Most of the decisions we make are just trades. We are trading one desirable experience for another. The people going to the gym or running the marathon are trading the experience of sitting back and relaxing, or doing something more desirable, for the experience of having all the benefits that exercising provides. My mom traded a more desirable, pain-free time, and desirable restful nights for the experience of having seven children and many grandchildren. Every decision we make we gain something more desirable.

The Star of Empowerment

Now, to the Star. Over the years, I noticed a pattern of behavior I labeled DAV, an acronym for Deny, Attack, Victim. At times, when people are confronted, they start with a denial, then they attack the person confronting them, and finally move to playing the victim. You will see this unhealthy pattern playing out over and over just about everywhere.

DAV will appear slightly different from situation to situation, but you will always observe the same pattern and the three roles. Here is a simple example to demonstrate this behavior. We have two individuals: we will call them Daver and Davee. Daver begins by yelling at Davee because they believe Davee is not listening to what they are saying.

Davee, not liking being yelled at, says, “Please don’t yell at me.” (The Confrontation)

Daver responds, “I’m not yelling.” Daver is denying doing what Davee observed and heard. (The Denial)

Daver continues, “Why would you say something like that?” Daver is now implying that Davee is the bad guy, or villain. (The Attack)

Next, Daver says, “I can’t believe you would say something about me like that; it really hurts me,” and now Daver is (The Victim).

In three quick steps, Davee went from someone attempting to improve the quality of the relationship to the villain. Daver transitioned from being the perpetrator to the victim, escaping all responsibility, and is now in a position where they most likely believe they are owed an apology, restitution, or that someone needs to be punished. Davee is often left dazed, confused, and frustrated.

Let’s consider a relatable scenario: being stopped by a police officer. Often, the initial response is some form of denial. “Why did you stop me? I wasn’t doing anything wrong. I wasn’t speeding, etc.” (Denial). Then, you might retort with “Don’t you have real criminals to go after?” (The Attack). Following the encounter, you spend the day recounting to others how a police officer unfairly issued you a citation for speeding as if you weren’t. (The Victim) You may even consider going to court and concocting a story about how your car’s speedometer isn’t working properly.

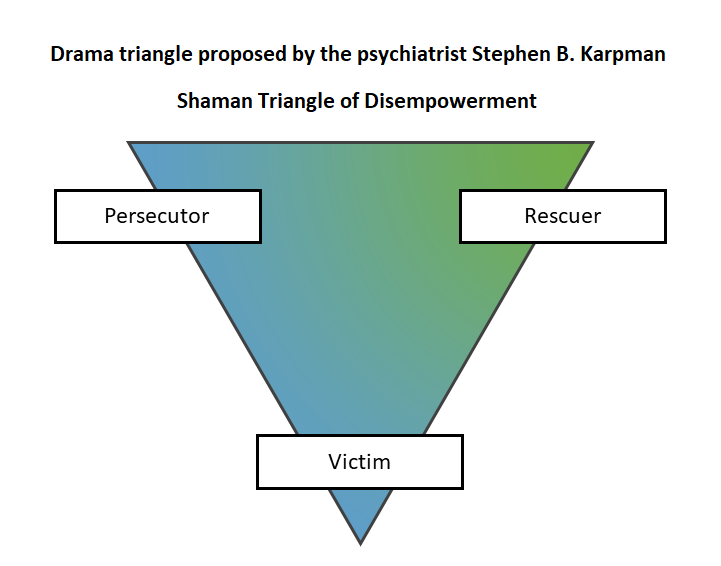

The Triangle of Disempowerment

One day, while sharing my observation of DAV with a shaman I was working with, she immediately drew a parallel between DAV and the Shamanic Triangle of Disempowerment.

I found the following description, which attributes the Triangle to the shamans, by Sivana East on her website at sivanaspirit.com

“The Triangle of Disempowerment is a map we can use to explore the roles we are playing and with whom. The three main characters involved in this triangle are the Victim, Rescuer, and Perpetrator. The goal is to step out of this web of dramas and back into our personal power and freedom. Often, we play one or more roles in any given situation or with any given person, switching back and forth among these roles, and sometimes embodying all three. In other words, we keep projecting the same parts and playing out the same patterns—usually with the exact same or similar characters, players, stories, and situations.”

“From this perspective, shamans understand that most problems we face result from our unhealed emotions. They believe that all perception is projection. We create the world around us at any given moment, dreaming our world into being each day as the conscious co-creators that we are.”

A similar concept was introduced by Stephen Karpman in the 1960s, called the Drama Triangle. It is a model of dysfunctional social interactions illustrating a power game involving three roles: Victim, Rescuer, and Persecutor, each representing a common and ineffective response to conflict.

More about the Drama Triangle can be found on the Leadership Tribe website at leadershiptribe.com

The Challenge With DAV and the Triangle

While DAV and the Triangle helped me recognize the behavior and its destructiveness, they didn’t provide insights into the underlying reasons or offer solutions. The shaman’s statement makes it sound simple: “The goal is to step out of this web of dramas and back into our personal power and freedom,” but I found it akin to having a flat tire with no clue how to change it. If someone told me my goal was to be back in my car, driving happily down the road, I would tell them I already understood that much.

In the weeks following the discussion with the shaman, I began to recognize three additional roles, for a total of six, that interact in all human thought, actions, and interactions, both healthy and unhealthy. I call these six roles the Hero, Judge, Performer, Victim, Villain, and Observer.

Thus, I created the Star of Empowerment to depict these roles and their interactions. I chose a star and the word empowerment for many reasons, but foremost as a tribute to the Triangle of Disempowerment, building upon it. I believe the Triangle effectively illustrates the three roles and how they disempower, while the Star empowers us by providing a map to understand what is happening with those disempowering roles and how to stop it, thereby empowering ourselves.

As I started to see my thoughts, actions, and interactions, as well as others through this paradigm, I start to notice how helpful it was. I found myself less frustrated, getting stuck less, and enjoying life more.

I decided to share the Star with a few people I know, thinking it might be interesting or useful to them. Immediately, I began receiving positive feedback. Over the following weeks, more positive reactions came in. I heard about the various situations in which people were using the Star to gain a new perspective, and the most rewarding feedback was how it positively affected their view of the world and the outcomes of situations they faced. This feedback led me to believe that the Star could be a powerful tool for many more people, and I felt compelled to work on making it more widely available. So, here it is.

The Roles

The concept of “The Star” is built on the idea that during any interaction—whether with ourselves or others—we embody one of six roles, or a blend of them. These roles are:

- The Hero

- The Judge

- The Observer

- The Performer

- The Victim

- The Villain

Initially, the notion of playing roles made me think of actors assuming personas that aren’t genuinely theirs. Striving to be as authentic as possible, I initially struggled with the idea that I might be “playing a role.” However, my perspective shifted once I understood that these roles aren’t about pretense but rather describe our focus at any given moment. For example, a doctor is always a doctor, a teacher is always a teacher, and an engineer is always an engineer. Yet, they only occupy these roles when they are performing their specific duties—caring for a patient, teaching, or designing something. Therefore, a role is defined by what we are primarily focused on at the moment.

These roles can manifest in healthy or unhealthy ways, being either empowering or disempowering. A healthy hero achieves and is recognized, which is both empowering and positive. Conversely, craving recognition as a hero without genuine achievement is unhealthy and disempowering. Similarly, being a victim can be a temporary, healthy state if it leads to receiving help, but playing the victim for sympathy or to manipulate others is unhealthy and disempowering. Essentially, genuinely inhabiting these roles is usually healthy; exploiting them for ulterior motives is not.

We engage with these roles internally in our thoughts and externally in the physical world.

The Hero

This role involves having rules and goals. Whether it’s washing a car with a detailed plan or deciding to drive to the car wash, heroes can operate solo or in teams, driven by various motivations like saving money or time.

The Judge

This role encompasses judgment, from evaluating what’s good enough to critiquing internally. It’s the voice that assesses our surroundings and our actions.

The Observer

Occupying the observer role allows us to fully experience and enjoy life. It’s the part of us that watches other roles play out, enabling us to create and make decisions free from fear.

The Performer

Any action we take puts us in the performer role. This can be an external action, like communicating or interacting with the world, or an internal process, like rehearsing conversations in our mind or visualizing outcomes.

The Victim

We assume this role when we’re hurt or feel threatened. While it’s natural to be a victim in certain situations, adopting this role unnecessarily or manipulatively can be counterproductive.

The Villain

Understanding this role is crucial; it doesn’t truly exist but is rather a perception. Recognizing this can significantly reduce stress and frustration, as the villain is often just a reflection of our fears and judgments.

Conflict – There are No Villains

Let’s address a common initial reaction: the skepticism around the assertion that there are no true villains in the world. When I discuss the dynamics of the Star and claim there are no villains, I am neither condemning nor condoning any behavior. The Star serves as a map or paradigm illustrating how the six different roles influence our thoughts, actions, and experiences—encompassing the good, the bad, and everything in between. Similar to how a road map shows connections and routes from one place to another without judging the destinations or the reasons for traveling, the Star demonstrates how human thought, actions, and interactions transition among roles without making judgments about them.

I believe the greatest benefit of the Star is its ability to transform how we view conflict and identify potential resolutions. This is crucial, as conflict acts as a destructive force, hindering our ability to achieve desired outcomes in life. Understanding conflict through the lens of the Star not only simplifies the other roles but also makes them more intriguing and accessible.

Recognizing the cause of conflict as explained by the Star leads us to the realization that there are no villains, only differing perspectives. A villain is merely a perception. Within each of us reside numerous ‘hero’ roles, and conflict—both external and internal—arises when two heroes, each with distinct goals, intersect. This is akin to two cars attempting to navigate an intersection simultaneously, each headed in a different direction.

Daver and Davee

Returning to the earlier DAV example helps illustrate why I assert there are no villains. Daver’s internal hero determined that yelling at Davee was the most effective method to achieve the goal of being heard. Conversely, Davee’s internal hero, aiming to protect themselves, intervenes to stop Daver from yelling. This is the juncture where two heroes clash, giving rise to conflict.

Davee ‘s hero disrupts Daver’s hero’s objective of feeling heard, and Daver’s hero, through denial, obstructs Davee ‘s protective hero. Daver’s intention was never to upset or harm Davee, just as Davee did not aim to prevent Daver from feeling heard. Yet, they both end up perceiving the other as a villain. This exemplifies the notion that there are no inherent villains, only two heroes colliding and subsequently viewing each other as the villain.

Had Daver or Davee recognized that Daver felt unheard and addressed that concern, the conflict could have been averted, allowing both parties to achieve their goals.

One of My Hero Stories

Consider a scenario where I approach a four-way stop sign in my minivan, accompanied by my wife, daughter, and two dogs, embodying the role of family protector. As I notice a vehicle approaching without intent to stop, I recognize the driver’s hero role might be driven by a desire to save time or alleviate frustration. Perhaps their adventurous hero is rushing to begin enjoying time with friends or family, or maybe their protective hero is hurrying to address a family emergency.

As they disregard the stop sign, I’m momentarily tempted to collide with their car, demonstrating how seriously my hero perceives the threat to my family’s safety. This reaction highlights the irrational lengths to which our heroes may go in pursuit of their objectives, especially concerning protection from harm. Fortunately, another one of my heroes intervenes, reminding me of the counterproductivity of such actions. Nonetheless, I might still express my disapproval through a prolonged horn honk or a hand gesture.

In this moment, his hero becomes my perceived villain, and I, in turn, become the villain to his hero. While I can never be certain of his thoughts, it’s unlikely he intended to cause harm by running the stop sign, despite how I might interpret his actions.

After my reaction, he probably doesn’t regard me positively, unlikely to appreciate my attempt to highlight the danger of his actions. More often than not, he’s likely responding with similar disdain, perpetuating the cycle of conflict.

No One Wants to be a Villain

No one enjoys being labeled a villain, as villains are often subjected to punishment, sometimes more severely than warranted. This is driven by a collective desire for fairness and the instinct to protect ourselves and others. Thus, anyone perceived as a villain quickly becomes a target, with few inclined to defend a punished villain. Common sentiments like “serves him right” or “he got what he deserved” reflect this mindset, leading to what I call a villain-victim scenario. This occurs when someone is victimized due to their perceived role as a villain, left to navigate their suffering alone, wary of further retribution.

What Causes Guilt

Have you ever gone to the freezer, spotted one of your favorite ice creams, and felt the internal battle commence? One part of you, let’s call it the I love ice cream hero, tempts you with how delicious it will taste. You might even be able to imagine the sensation of eating it, anticipating the flavor as it touches your tongue. Then, a your health-conscious hero steps in, reminding you of all the reasons why the ice cream is a poor choice. It warns you about the imminent sugar crash and potential long-term health consequences. Perhaps you even visualize the numbers on the scale during your next weigh-in, or how you’ll feel physically afterwards. This is the internal conflict between two heroes with opposing goals.

To delve into guilt, let’s say you decide to indulge and eat the ice cream. The hero advocating for the treat has triumphed and recedes into the background, its mission accomplished. However, the hero that advised against it remains, dissatisfied with the outcome. It lingers, persistently reminding you of all the reasons why you should have heeded its advice, lamenting the decision to indulge. This hero dislikes failure and is determined to prevent similar choices in the future. As you and your indulgent hero relish the ice cream, you inadvertently cast the health-conscious hero as the villain. Now, you’re left with this disappointed hero, seizing every chance to remind you of your supposed misstep, casting you as a villain-victim. This persistent feeling of regret and self-reproach? That’s guilt.

Why Guilt is Used the Most to Manipulate People

The simple answer is that it is the most effective way. But, as stated earlier, people want to avoid being a villain-victim more than anything else. Who wants to put themselves in a situation where they are suffering, people will be happy to add to their suffering, and where it is highly unlikely that no one is going to help them. So, if you want the best chance of getting someone to do something, or not do something, just communicate to them the troubles they are going to create for themselves, and our natural systems will do the rest.

This is the same dynamic at work when it comes to FOMO, or fear of missing out. It’s not the desire for the thing we might not get that drives us, it’s the desire to avoid being our own villain-victim. If you think back, my guess is that you can clearly remember a few times that you have experience FOMO, but can’t remember if you missed out or not, or if that thing is still in your life.

Back to DAV

Once I had the Star map, the why and how of DAV became so clear. It starts when 2 heroes with different objectives cross paths. The Denial happens because no one wants to be a villain-victim. The Attack, because the other person’s hero is now the Daver’s villain and the Daver is protecting themselves from becoming the villain-victim. It also shuts down the Davee because they now feel the fear of becoming a villain-victim. Then the Daver switches to the Victim, when someone is seen as a victim, most people will have sympathy for them and will want to help them. So, the Daver is now safe from being seen as the villain-victim, and back in a position where they may be able to achieve a goal, or at a minimum, where no one is going to try to punish them. So, it is far better to be seen as a victim, than a villain-victim. Denying, attacking, and portraying themselves as the victim is the most effective way to do that.

The Criminal Jury System

Seeing the world through the star of empowerment has been and continues to be an incredible experience. I continually see the dynamics everywhere I look. One of the things that jumped out at me was the Criminal Jury Trial system. The system is comprised of the 6 roles in the star. We have the hero (law enforcement), the performer (the lawyers), the perceived villain (the defendant), the victim (victim), the judge (judge), and the observer (the jury).

Law enforcement in the hero role as protector, with its evidence as presented by its performer, the prosecutor, will make its case as to the guilt of the defendant to convince the observer, the jury to join them as heroes. The perceived villain, the defendant, will present evidence via its performer to show they are innocent.

The judge will monitor everyone making sure the rules are followed and stepping in as needed. Just as our internal judge is monitoring things and letting us know when things don’t add up. This role in us is always working to keep things fair, balanced, and on track.

The jury as the observer will observe all the other roles just as our observer does. They will evaluate all their prior experiences, and what they observe during the trial. Then they will be given the opportunity to become heroes at the end by making the final decision of guilt or innocence. Just as we, in the observer role make the final decision about what our heroes, judge, and performers tell us. If they find the defendant guilty, they will join law enforcement and the judge, and all will be heroes because they are protecting the victim and possible future victims. They may also feel like heroes because they are helping to punish the villain and creating balance in the world because of our innate need for fairness. Of course, they have now become the defendant’s villain.

Should they find not guilty, they are still heroes along with the judge because they have saved the perceived villain from becoming a victim of law enforcement. They will also most likely move into the role of villain to the victim.

Five Worlds

The Five Worlds

Every day, we navigate and attempt to align five distinct worlds:

- The Real World.

- The Perceive World.

- The Should World.

- The My Future World.

- The Other’s World.

The Real World

From its name, you can probably guess what the Real World is. Yes, it’s the world that exists independently of our perceptions. None of us know exactly what that entails, but we all acknowledge its existence. If your first thought is about the unknown aspects of the universe or its complexity, that too falls under the Real World. If there is something that we are not aware of yet, that does not change the Real World, just our perception of it.

The Perceive World

The Perceived World, as you might guess, is the world as we perceive it. This world is shaped by our senses, experiences, beliefs, and biases.

The Should World

The Should Be World presents some of our biggest challenges. It consists of all the things we believe should happen. For example, everyone should stop at red lights, wait their turn in line, respect each other, not steal, and drive within the speed limit. These “shoulds” come from various sources, including the rules we’ve learned and our experiences. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with these beliefs (indeed, many of them are also my own), it’s crucial to recognize how this world influences us. I recall sitting at a red light, waiting to turn left, when someone sped through the red light using the center lane. Initially angered, I reminded myself that the Real World and my Should Be World don’t always align, and the anger subsided.

The Future World.

The Future World is the world we are striving to create for ourselves. This includes the job we want, the house we dream of, the spouse we seek, the vacations we plan, and the relationships we desire. It encompasses all the things we are actively working to manifest in our lives.

The Other’s World

The Other’s World is more dynamic, than the others, as it is composed of many changing worlds, yet we experience it as a singularity, which is why it is considered a single world to each of us. This world emerges from our interactions with others, whether it be with one person or within a group.